This Is Part 1/2 of Building a Sustainable Future with Thermal Energy Networks by Marc Miller, Egg Geo, LLC

Modern energy demands are growing, and the need for sustainable, efficient solutions to heat and cool our homes and businesses has never been greater. Enter Thermal Energy Networks (TENs)—innovative systems that distribute and reuse energy to reduce costs, cut emissions, and optimize performance.

Image: Eversource

This article explores the basics of TENs, their benefits, and real-world applications, helping you understand their potential to transform energy systems for the better.

What Are Thermal Energy Networks?

At their core, TENs are district energy systems that use ambient temperature loops (ATLs) to share heating and cooling between buildings. These loops typically circulate a heat transfer fluid, such as water or a water-propylene glycol mixture, at a temperature range of 50°F to 85°F. By tapping into diverse thermal sources, such as geothermal wells, waste heat recovery, or natural water bodies, TENs provide sustainable, cost-effective alternatives to traditional heating and cooling systems.

Crucially, TENs optimize thermal sharing between stakeholders:

- Consumers exclusively use thermal energy.

- Prosumers both produce and consume energy (e.g., offices that generate heat and reuse it internally).

- Generators supply thermal energy into the network (e.g., geothermal wells or industrial processes).

How TENs Are Different?

Unlike traditional systems like two-pipe or four-pipe setups of district heating and cooling scenarios, TENs use an ambient one-pipe loop that operates at variable fluid flow and temperatures instead of relying on constant temperature and variable flows. Here’s what sets TENs apart:

- One-Pipe Systems manage heating and cooling directly by varying the flow of the fluid of varying temperature circulating the loop.

- Efficiency in Pumping reduces energy waste with self-balancing, simpler designs that eliminate the need for balancing valves. This results in significantly lower operating and installation costs.

- Pump Controlled Instead of Valve Controlled. No balance valves or control valves are used. Flow through decoupled secondary loops is managed by a pump sized to deliver the optimal flow.

Key Benefits of TENs

Energy Efficiency

TENs enable efficient thermal load sharing and shedding. For example:

- Unused heat from one building can be redistributed to another, maximizing energy use across the network.

- Water source heat pumps (WSHPs) leverage the stable temperature of ATLs, operating with coefficients of performance (COP) ratings of 3–5, which translate to lower energy consumption.

Cost Savings

Compared to traditional systems, TENs offer significant financial benefits:

- Lower Installation Costs: With single-pipe systems, there’s less piping, no balancing or control valves, and reduced labor for installation because of less fittings, less tooling and overall less pipe. Additionally there is a single pipe size for the entire loop.

- Reduced Operating Costs: Circulating water at ambient temperatures requires much less pumping power.

Scalability and Flexibility

TENs are highly scalable—there’s no limit to the number of stakeholders that can connect to an ATL. The caveat is that when sizing the loop, it must be sized for the total load to include anticipated future expansion. The more buildings added, the better the system operates due to improved thermal diversity, which counterbalances the temperature cascade effect (where fluid temperatures progressively change as they circulate).

Environmental Impact

Integrating geothermal energy with TENs significantly reduces greenhouse gas emissions. By shifting away from fossil-fuel-based heating systems, TENs pave the way for a green and sustainable future.

Real-World Example

The Eversource Geothermal Pilot in Framingham, Massachusetts, is a first-of-its-kind utility-scale networked geothermal project. Launched in 2024, this system connects 135 residential and commercial buildings, providing ground-sourced heating and cooling through an ambient temperature loop.

Key takeaways from this pilot include:

- Reduced reliance on fossil fuels, replaced with renewable energy from earth’s natural thermal stability.

- Positive feedback from participating stakeholders due to noticeably reduced energy costs and environmental impact.

- A replicable model for other communities to follow.

“This project… is enabling our team to see how we can provide services in a completely new way,” shared Bill Akley, President of Gas Distribution at the project’s groundbreaking.

Challenges and Considerations

No system is without challenges, but TENs offer practical solutions for common concerns.

- Temperature Cascade Effect: Concerns about progressive temperature changes are resolved by system diversity. More connected stakeholders create a smoothing effect that distributes thermal loads more evenly.

- Initial Investment: Modern legislative incentives and community grants, like those funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, are now making upfront costs more affordable for communities adopting TENs.

How TENs Function, a Simple Explanation

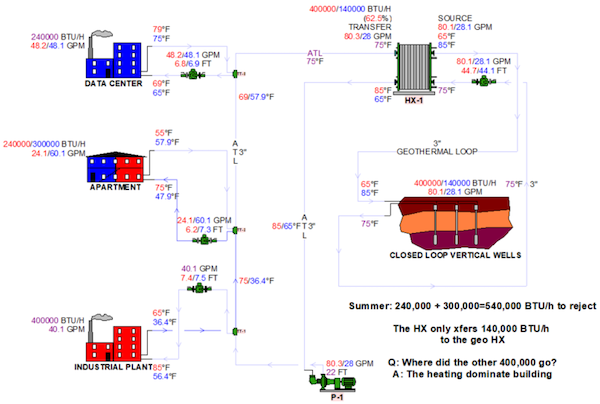

In the first illustration below, a TEN utilizing its one-pipe Ambient Temperature Loop (ATL). The TEN consists of a geothermal source/sink, an intermediary heat exchanger, a main loop distribution pump, and three stakeholders: a cooling-dominant data center, a heating-dominant industrial plant, and an apartment building with relatively balanced heating and cooling loads.

During the summer, the network manages a total heat rejection of 540,000 BTU/h from the apartment building and the data center. However, only 140,000 BTU/h is transferred to the geothermal sink via the heat exchanger (HX-1). This reduction occurs because the network redirects excess heat to the industrial plant, utilizing it for productive purposes rather than rejecting it to the ground.

In winter, the network requires a total of 640,000 BTU/h to meet the heating demands of the apartment building and the industrial plant. Of this, 400,000 BTU/h is supplied by the geothermal source through HX-1, while the remaining 240,000 BTU/h is provided by the data center, offsetting the geothermal demand. This demonstrates the network’s ability to efficiently balance loads by redistributing energy among stakeholders.

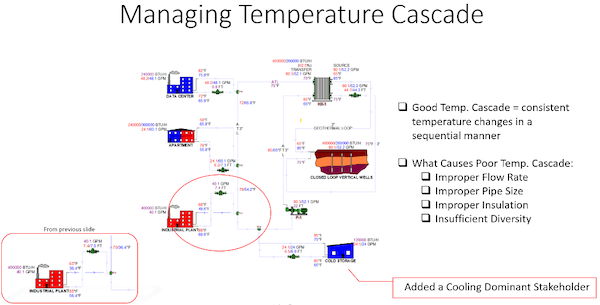

In the second example below, we introduce a cooling-dominant load of approximately 10 tons (120,000 BTU/h) to the loop. The system is designed to maintain a leaving heat exchanger temperature of 65°F and a return temperature of 75°F, preserving a 10°F delta T. This consistency is achieved through pump control. By increasing the pump speed and actively managing water flow through the heat exchanger based on temperature, the system sustains the desired 10°F delta T. foundational principles of a TEN.

The performance of such a network improves with greater load diversity, i.e., the inclusion of more stakeholders with varying thermal profiles. Additionally, since the system is pump-controlled and does not rely on balancing valves the system is self-balancing. In fact, the temperature cascade effect is shown to improve with an increasing number of thermally diverse stakeholders connected to the loop.

In the previous scenario, the pump’s flow rate was 28 GPM. With the added load, it increases to 54 GPM. Additionally, the inlet temperature to the industrial plant rises from 56.4°F to 69.6°F. Even with the extra 10 tons of cooling load, the pipe size for both the geothermal source/sink loop and the ambient temperature loop remains 3 inches. Importantly, the return temperature to the heat exchanger remains consistent at a 10°F delta T with a 75℉-return design temp.

By examining the ambient temperature loop (ATL), we observe that the temperature range improves significantly, aligning with the target range of 55°F–85°F. Previously, when there were only three loads, the loop’s temperature immediately after the industrial plant was much lower at 36.4°F. Furthermore, the heat transfer through HX-1 and the geothermal well field increases substantially, from 140,000 BTU/h to 260,000 BTU/h, reflecting the additional 10 tons of cooling load.

It is worth noting that this theoretical scenario assumes no other consumers of waste heat, providing just a snapshot in time. In practice, there will always be various heat consumption requirements, such as domestic hot water production, pool heating, or snow melting. Thermal energy networks (TENs) are designed not only for heating and cooling but also for these additional purposes. As a result, the BTUs from cold storage will be utilized across multiple applications beyond simple heating or cooling thus keeping the amount of heat to be rejected by HX-1 to a minimum

This simplified explanation underscores the system’s ability to adapt to increased loads while maintaining efficiency and highlights the versatility of thermal energy networks in meeting diverse energy demands. In part 2 of this article, we will dive into the specifics of how to connect your home or building to the TEN with a decoupled secondary loop and talk about how to control the pump to account for Thermal Diversity and Temperature Cascade Effect.

Marc Miller is a Mechanical Systems SME – Educator – Technical Writer – Author – Construction Management Consultant with Home – Egg Geo. He is presently the Lead Author on two textbook projects with Egg Geo. He may be reached at marcm@egggeo.com.

Marc Miller is a Mechanical Systems SME – Educator – Technical Writer – Author – Construction Management Consultant with Home – Egg Geo. He is presently the Lead Author on two textbook projects with Egg Geo. He may be reached at marcm@egggeo.com.