The oyster appetizer tray made its way around the table during our group dinner, and I asked the guy sitting next to me if he wanted first dibs, to which he replied, “No thanks, I know where they’ve been.” I mean, I kinda knew, but maybe not as much as this guy? So I declined Read more

respiratory disease

The oyster appetizer tray made its way around the table during our group dinner, and I asked the guy sitting next to me if he wanted first dibs, to which he replied, “No thanks, I know where they’ve been.” I mean, I kinda knew, but maybe not as much as this guy? So I declined, as well.

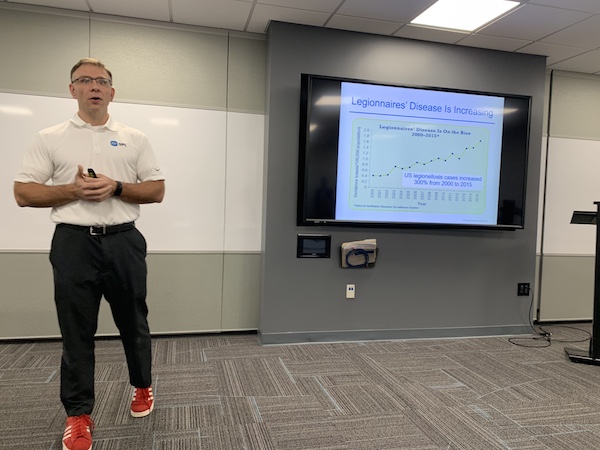

Turns out, “that guy” sitting next to me was Frank Sidari, PE, BCEE, Technical Director, Special Pathogens Laboratory (SPL), and one of the featured speakers at a recent Watts Water Technologies Healthcare Symposium. Sidari was there to speak about Legionella and its growth, and the growing concern in the industry.

“No one should die from a preventable disease caused by bacteria in water,” said Sidari, suggesting that Legionnaires’ Disease is on the rise. Part of this rise correlates to the fact that there wasn’t really any testing being done for Legionella. Yet, it’s one of those “It’s never going to happen to me”-type diseases. What could have been mistaken for other ailments, the disease was often times diagnosed as pneumonia or the flu in older people, or those with auto-immune disorders.

According to the SPL presentation, public water supplies may contaminate the plumbing systems of hospitals and other large buildings. In fact, Legionella bacteria is not ubiquitous, but are found in 50% of building water systems—not all—which consist of:

- 12-70% of hospital water systems

- Up to 60% of large high-rise buildings

- 10-40% of residential homes

- 30-50% of cooling towers colonized with Legionella

Legionella can be found in building warm water systems such as faucets, showers, hot water tanks, decorative fountains, pools, spas and cooling towers, for example.

Transmission of pathogenic Legionella in the water system is the aerosolization and aspiration from an environmental source into the lungs—when the exposure to contaminated water reaches the airways—and because it is chlorine tolerant, it can survive the water treatment process and pass into the water distribution system. It grows in the water systems in the right conditions, i.e. water temperature, sediment and commensal microbes. Again, the disease can occur if the host is susceptible.

Frank Sidari

Variables such as water flow, distribution, velocity and temperature and play an important part for risk reduction. Risk factors such as water supply, building use and size, system design and hot water set-up all contribute to a safe and effective plumbing system.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention has reported that Legionella accounted for 66% of reported drinking water-associated outbreaks, and Legionella in building plumbing systems lead to drinking water-associated outbreaks.

As there has been movement for the Center of Disease Control to develop a water management program to reduce Legionella growth in buildings, Illinois senators, for example, sent a letter to the leaders of three health-related agencies—the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the EPA—asking for their help in responding to a Legionnaires’ disease outbreak at a state-run veterans home, in Manteno, says Dain Hansen, Senior Vice President, Government Relations, The IAPMO Group.

This comes on the heels of a Legionnaires’ disease outbreak at an Illinois veterans’ home in Quincy that killed 14 people since 2015.Traction is being made in Illinois. “In response to the ongoing crisis, Illinois’ new governor, J.B. Pritzker, has established a Legionnaires’ disease task force, and the senators also requested that the three federal agencies participate in that effort,” says Hansen.

In New York state, environmental assessments are required with a Legionella sampling and risk management plan is in place where <30% distal outlet positivity requires corrective action.

Industry-wide, ASHRAE Standard 188, the first Legionella standard in the U.S., which was approved in 2015 and revised in 2018, establishes minimum Legionellosis risk management requirements for building water systems.

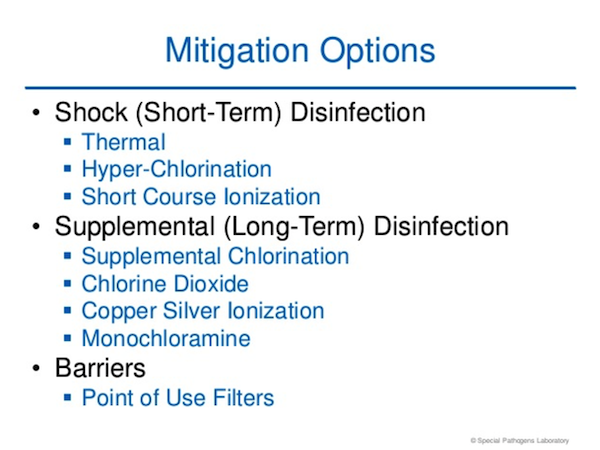

According to the Special Pathogens Laboratory, zero Legionella is virtually impossible to achieve in complex water systems so zero cases is the goal, not zero Legionella through Legionella control. The SPL suggests that in hospitals and long-term care facilities—and other facilities I would presume—establishing water management policies to reduce the risk of growth and spread of Legionella and other opportunistic pathogens, conducting a risk assessment and implementing a water management program are all very good ideas for a facility.

Each building owner must assess the risk and validate their water management plans to demonstrate control of the hazard. The SPL suggests that in hospitals and long-term care facilities—and other facilities, I would presume—establishing water management policies to reduce the risk of growth and spread of Legionella and other opportunistic pathogens, conducting a risk assessment and implementing a water management program are all very reasonable considerations for a facility.

Source: Special Pathogens Lab